What are the Highlights of the Survey? - Social Issues | UPSC Learning

Topics

0 topics • 0 completed

🔍

No topics match your search

What are the Highlights of the Survey?

Medium⏱️ 8 min read

social issues

📖 Introduction

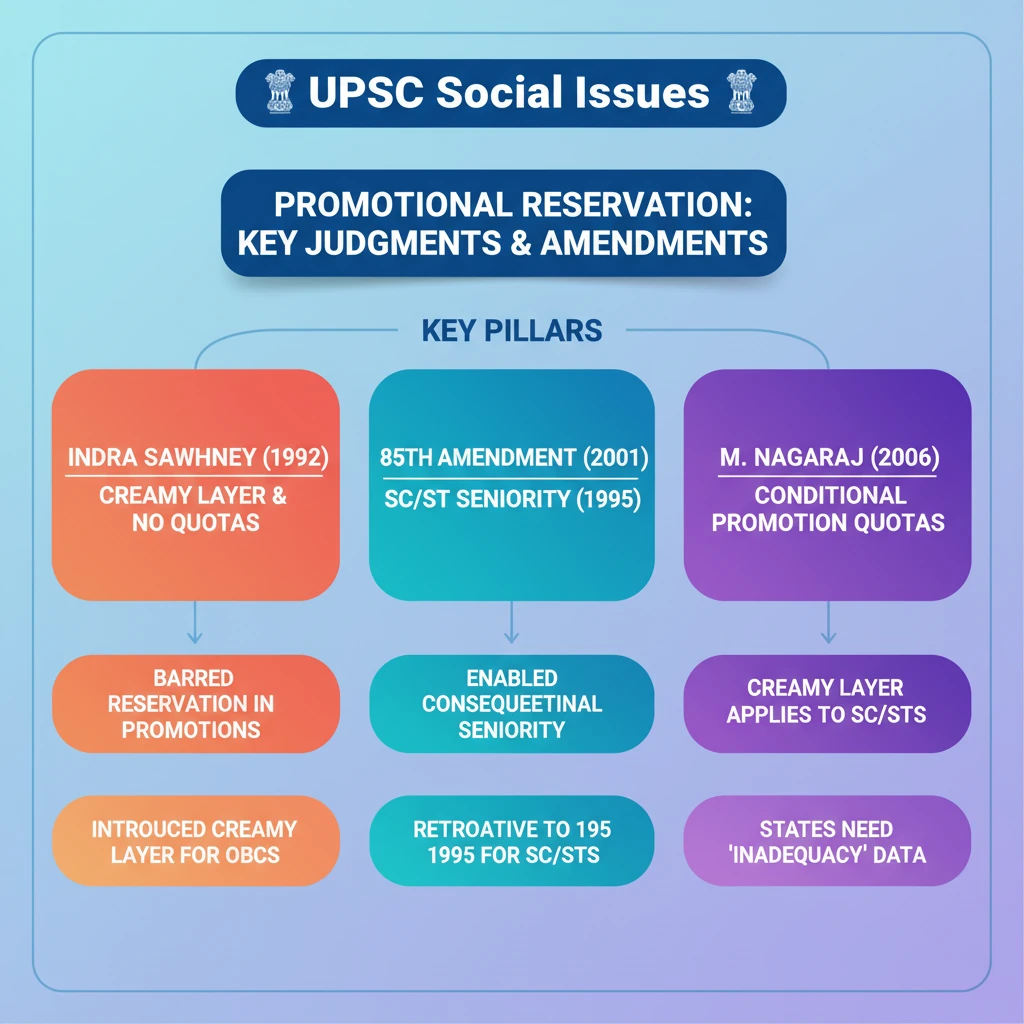

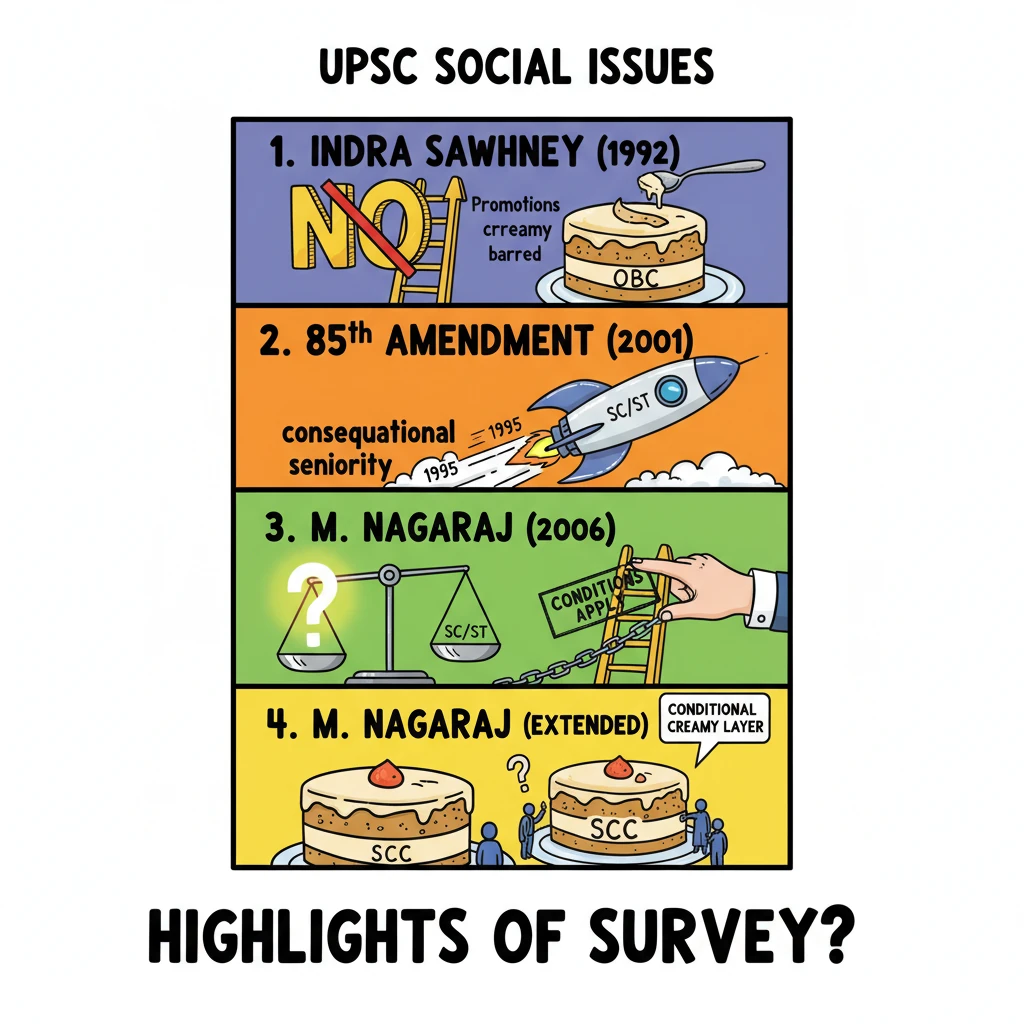

<h4>Understanding Reservation in Promotions: Key Judgments and Amendments</h4><p>The issue of <strong>reservation in promotions</strong> for various communities has been a significant and complex legal and social debate in India. Several landmark judgments and constitutional amendments have shaped its current framework, aiming to balance the principles of <strong>equality of opportunity</strong> and <strong>social justice</strong>.</p><h4>The Indra Sawhney Judgment (1992)</h4><p>The <strong>Indra Sawhney v. Union of India</strong> case, popularly known as the <strong>Mandal Commission case</strong>, was a pivotal moment in India's reservation policy. A <strong>9-judge bench</strong> delivered this landmark judgment.</p><div class='info-box'><p>The judgment held that <strong>Article 16(4)</strong> of the Constitution, which allows reservation in appointments, <strong>does not extend to promotions</strong>. This was a critical ruling that initially restricted reservations only to initial appointments.</p></div><p>The court affirmed the validity of the <strong>carry forward rule</strong> for unfilled reserved vacancies but stipulated that it must remain subject to the overall <strong>50% ceiling</strong> on reservations. This ensured that reservations do not exceed a reasonable proportion.</p><div class='key-point-box'><p>A significant clarification was made regarding the relationship between <strong>Article 16(1)</strong> and <strong>Article 16(4)</strong>. The court stated that <strong>Article 16(1)</strong>, guaranteeing <strong>equality of opportunity</strong>, is a <strong>fundamental right</strong>, while <strong>Article 16(4)</strong> is merely an <strong>enabling provision</strong> and not a separate rule overriding 16(1).</p></div><div class='info-box'><p><strong>Article 16(1):</strong> "It states that there shall be <strong>equality of opportunity</strong> for all citizens in matters relating to employment or appointment to any office under the State."</p></div><p>Furthermore, the judgment directed the exclusion of the <strong>Creamy Layer</strong> (economically well-off) from <strong>Other Backward Classes (OBCs)</strong> from receiving reservation benefits. This aimed to ensure that the benefits reach the most deserving within the backward classes.</p><p>However, the court specifically excluded <strong>Scheduled Castes (SCs)</strong> and <strong>Scheduled Tribes (STs)</strong> from the application of this <strong>creamy layer concept</strong> at that time.</p><h4>The 85th Amendment Act (2001)</h4><p>To address the implications of the <strong>Indra Sawhney judgment</strong>, particularly concerning promotions, the Parliament enacted the <strong>85th Amendment Act</strong> in <strong>2001</strong>.</p><div class='info-box'><p>This amendment introduced the concept of <strong>consequential seniority</strong> for <strong>SC/ST candidates</strong> promoted through reservations. It allowed these candidates to retain their seniority over general category candidates who might have been senior to them in the feeder cadre but were promoted later.</p></div><p>The amendment applied retroactively, effective from <strong>June 1995</strong>, meaning its provisions could be applied to promotions made after that date.</p><div class='info-box'><p><strong>Consequential Seniority:</strong> Refers to the concept of granting seniority to government servants belonging to <strong>SC</strong> and <strong>ST</strong> in cases of promotion through reservation rules.</p></div><h4>M. Nagaraj Judgment (2006)</h4><p>The <strong>M. Nagaraj v. Union of India</strong> judgment in <strong>2006</strong> was another significant ruling that revisited the issue of reservation in promotions, particularly after the <strong>85th Amendment</strong>.</p><div class='key-point-box'><p>This judgment partially overturned the <strong>Indra Sawhney judgment</strong> by allowing states to provide reservations in promotions for <strong>SCs/STs</strong>, but with certain conditions.</p></div><p>Crucially, the <strong>M. Nagaraj judgment</strong> introduced a conditional extension of the <strong>"creamy layer" concept</strong> to <strong>SC/ST communities</strong> seeking promotions in government jobs. This concept was previously applied only to <strong>Other Backward Classes (OBCs)</strong>.</p><p>The judgment laid down <strong>three conditions</strong> to allow states to provide reservations in promotions for <strong>SCs/STs</strong>. The first condition explicitly mentioned is:</p><ul><li><strong>Inadequacy of Representation:</strong> The state must demonstrate that <strong>SCs/STs</strong> are inadequately represented in promotions within the public services.</li></ul><div class='exam-tip-box'><p>Understanding the evolution of reservation policy through these judgments and amendments is crucial for <strong>UPSC Mains GS Paper II (Polity & Governance)</strong>. Focus on the core principles, the changes introduced, and the conditions laid down by the Supreme Court.</p></div>

💡 Key Takeaways

- •Indra Sawhney (1992) initially barred reservation in promotions and introduced creamy layer for OBCs.

- •85th Amendment (2001) enabled consequential seniority for SC/STs in promotions, retroactive to 1995.

- •M. Nagaraj (2006) partially overturned Indra Sawhney, allowing conditional reservation in promotions for SC/STs.

- •M. Nagaraj extended creamy layer concept conditionally to SC/STs for promotions.

- •States must provide quantifiable data on 'inadequacy of representation' for SC/STs to implement promotional reservations.

🧠 Memory Techniques

95% Verified Content