SC Allows for Sub-Classification of SCs and STs - Social Issues | UPSC Learning

Topics

0 topics • 0 completed

🔍

No topics match your search

SC Allows for Sub-Classification of SCs and STs

Medium⏱️ 8 min read

social issues

📖 Introduction

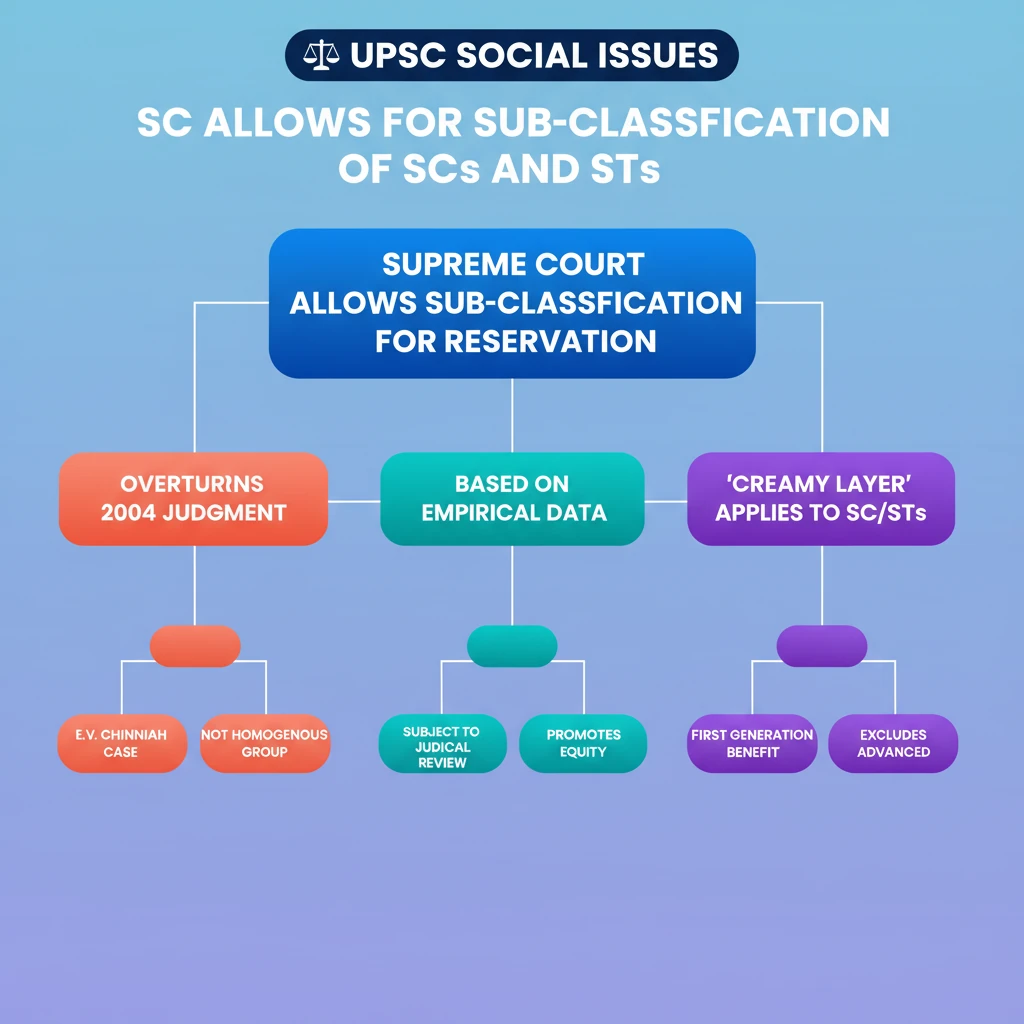

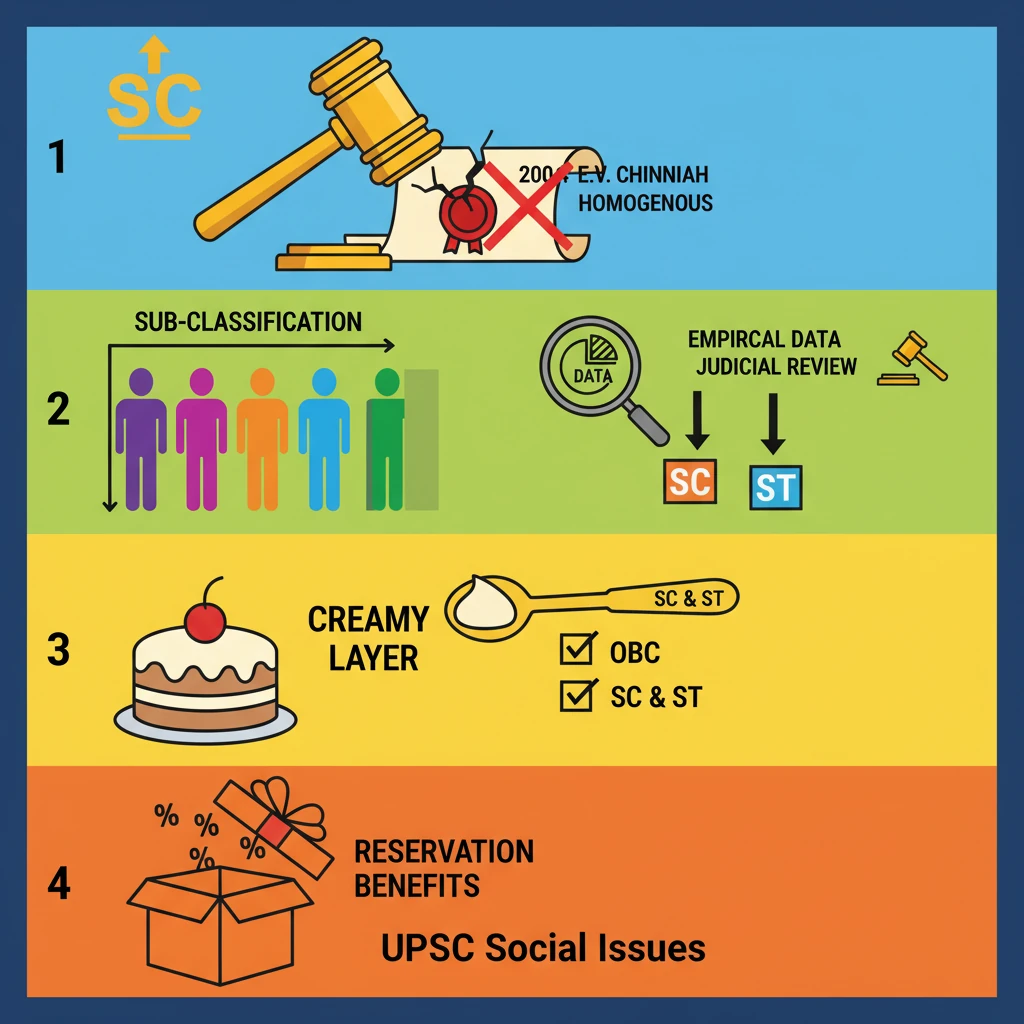

<h4>Introduction to Sub-Classification Verdict</h4><p>The <strong>Supreme Court of India</strong> has delivered a landmark verdict, allowing states the authority to <strong>sub-classify reserved categories</strong> like <strong>Scheduled Castes (SCs)</strong> and <strong>Scheduled Tribes (STs)</strong>. This decision is crucial for tailoring reservation policies to better serve the most disadvantaged groups within these categories.</p><p>This ruling fundamentally alters the landscape of reservation policies, aiming to ensure benefits reach those who are truly in need. It addresses the internal disparities and varying levels of backwardness within the broader SC and ST classifications.</p><div class="info-box"><p><strong>Contextual Note:</strong> Tribes like the <strong>Kondulu</strong> are often endogamous, divided into groups such as <strong>Pedda Kondulu</strong> and <strong>China Kondulu</strong>, each with several clans. Modernization and cultural contact are transforming their traditional lifestyles, highlighting the need for nuanced policies.</p><p>The <strong>Lower Sileru Hydro Electric Project</strong>, a <strong>460 MW hydro power project</strong> on the <strong>Sileru river</strong>, is situated in a dense forest in the agency area of <strong>Visakhapatnam, Andhra Pradesh</strong>, impacting tribal communities.</p></div><h4>The Landmark Supreme Court Ruling</h4><p>A <strong>six-to-one majority decision</strong> by the <strong>Supreme Court of India</strong> has overturned its own <strong>2004 ruling</strong> in <strong>E.V. Chinniah vs. State of Andhra Pradesh</strong>. This verdict grants states the power to create sub-classifications within <strong>SCs</strong> and <strong>STs</strong> for reservation purposes.</p><div class="key-point-box"><p>The seven-judge Bench ruled that states can now sub-classify <strong>SCs</strong> within the <strong>15% reservation quota</strong>. This aims to provide more targeted support for the most disadvantaged groups, ensuring equitable distribution of benefits.</p></div><h4>Key Provisions of the Verdict</h4><h5>Sub-Classifications Permitted</h5><p>The Court ruled that states are constitutionally allowed to sub-classify <strong>SCs</strong> and <strong>STs</strong> based on varying levels of backwardness. This allows for a more granular approach to reservation benefits.</p><p>The <strong>Chief Justice of India</strong> emphasized the distinction between “<strong>sub-classification</strong>” and “<strong>sub-categorisation</strong>.” He cautioned against using these classifications for mere political appeasement, stressing that the goal must be genuine upliftment.</p><h5>Empirical Data and Judicial Review</h5><p>The Court noted that any sub-classification must be based on <strong>empirical data</strong> and <strong>historical evidence of systemic discrimination</strong>. Arbitrary or politically motivated reasons are not permissible.</p><p>States must base their sub-classification decisions on robust empirical evidence to ensure both fairness and effectiveness. Furthermore, state decisions on sub-classification are subject to <strong>judicial review</strong> to prevent any potential political misuse.</p><div class="info-box"><p><strong>Important Clarification:</strong> The Court clarified that <strong>100% reservation</strong> for any single sub-class is not permissible. This maintains the principle of proportionality and avoids monopolization of benefits.</p></div><h5>Application of Creamy Layer Principle</h5><p>The <strong>Supreme Court</strong> has ruled that the ‘<strong>creamy layer</strong>’ principle, previously applied only to <strong>Other Backward Classes (OBCs)</strong> as highlighted in the <strong>Indra Sawhney Case</strong>, should now also be applied to <strong>SCs</strong> and <strong>STs</strong>.</p><p>This means states must identify and exclude the <strong>creamy layer</strong> within <strong>SCs</strong> and <strong>STs</strong> from reservation benefits. This ensures that the benefits reach those who are truly disadvantaged and not those who have already achieved a certain level of advancement.</p><h5>First-Generation Limitation</h5><p>The Court stated that <strong>reservation benefits</strong> should primarily be limited to the <strong>first generation</strong>. If any generation in a family has already taken advantage of reservation and achieved a higher status, the benefit would not logically be available to the second generation.</p><div class="exam-tip-box"><p>This aspect of the judgment is crucial for ensuring that reservation policies serve their intended purpose of upliftment, rather than becoming a perpetual entitlement for successive generations within a family. It promotes equitable access for those who are yet to benefit.</p></div><h4>Rationale for Allowing Sub-Classification</h4><p>The Court acknowledged that systemic discrimination often prevents some members of <strong>SCs</strong> and <strong>STs</strong> from advancing. Therefore, <strong>sub-classification</strong> under <strong>Article 14</strong> of the Constitution can help address these disparities more effectively.</p><p>This nuanced approach allows states to tailor reservation policies. It ensures that support is more effectively directed towards the most disadvantaged groups within the larger <strong>SC</strong> and <strong>ST</strong> categories, promoting a more equitable distribution of opportunities.</p><h4>Origin of the Sub-classification Issue</h4><p>The issue of sub-classification of <strong>Scheduled Castes (SCs)</strong> was initially referred to a <strong>seven-judge bench</strong> by a <strong>five-judge bench</strong> in the case of <strong>State of Punjab v. Davinder Singh (2020)</strong>. This referral was a pivotal moment in the legal journey of reservation policy.</p><p>The primary factor leading to this referral was the need to reconsider the judgment in <strong>E.V. Chinniah v. State of Andhra Pradesh (2004)</strong>. The earlier ruling had significantly restricted the scope for states to implement nuanced reservation policies.</p><h4>Overturning E.V. Chinniah vs. State of Andhra Pradesh (2004)</h4><p>The <strong>E.V. Chinniah ruling</strong> had previously stated that sub-classification within <strong>SCs</strong> was not permissible. The rationale then was that <strong>SCs</strong> formed a <strong>homogenous group</strong>, implying a uniform level of backwardness.</p><div class="key-point-box"><p>The recent <strong>Supreme Court verdict</strong> directly overturns this earlier interpretation. It recognizes that <strong>SCs</strong> and <strong>STs</strong> are not homogenous groups and exhibit varying degrees of backwardness, necessitating a more flexible and targeted approach to reservations.</p></div>

💡 Key Takeaways

- •Supreme Court allows states to sub-classify SCs and STs for reservation benefits.

- •This overturns the 2004 E.V. Chinniah judgment, which considered SCs a homogenous group.

- •Sub-classification must be based on empirical data and is subject to judicial review.

- •The 'creamy layer' principle, previously for OBCs, now applies to SCs and STs.

- •Reservation benefits are primarily for the first generation, excluding those who have already achieved higher status.

- •The verdict aims for more equitable and targeted distribution of reservation benefits to the truly disadvantaged.

🧠 Memory Techniques

98% Verified Content

📚 Reference Sources

•Supreme Court of India judgments (E.V. Chinniah vs. State of Andhra Pradesh, State of Punjab v. Davinder Singh, Indra Sawhney Case)

•Constitutional provisions related to reservation (Articles 14, 15, 16)